BECAUSE THE UNAWARE ARE

UNAWARE THAT THEY ARE UNAWARE:

|

Partners |

Main Archives & Search |

News World Order |

News World Order

Mirrored Articles

FAIR USE NOTICE:

This site contains copyrighted

material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by

the

copyright owner. We are making

such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental,

political, human

rights, economic, democracy, scientific,

and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use'

of any such copyrighted

material as provided for in section

107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section

107, the material on

this site is distributed without

profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included

information for research

and educational purposes. For more

information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

If you wish to use

copyrighted material from this

site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain

permission

from the copyright owner

This is a mirrored article

Paranoid Nation

by Gary Indiana

No Such Thing as Paranoia

On the culture of conspiracism

part 1 of 3

Like conspiracies themselves, conspiracy

theories are as old as gossip and politics. To understand the world one

inhabits, it is impossible to credit the idea of contingency or chance

as the root of all weirdness. Just as any psychotic tends to utter something

true in the process of saying something crazy, there is usually a kernel

of reality in even the most far-fetched conspiracy theory.

While it is easy to distinguish a belief that aluminum foil wrapped around one's head filters out alien brain waves from rational but dissident ideas, some modern writers on conspiracy theory tend to conflate nonconformity with the most bizarre and cognitively defective extremes of it. So-called "consensus historians," following the lead of Richard Hofstadter's famous 1964 essay, "The Paranoid Style in American Politics," have effectively pathologized any suspicion of active conspiracies, however defined, into a synonym for "nut job" in public discourse.

Our mass media, its ownership consolidated among a handful of billionaires whose interests are identical with those of corporate cronies (globalized "free trade" for the wealthy nations, peonage for the third world, Chomsky's "manufacture of consent" via a constant torrent of propaganda for the status quo), reflexively dismiss the most obvious or credible explanations for ugly phenomena as the perfervid fantasy of "conspiracy cranks"—for instance, the idea that successive "preemptive" wars might be launched against demonized enemies in order to award reconstruction contracts to corporations formerly helmed by, say, the vice president of the United States and other exalted government employees, or that the strategic purpose of one such war might be the economic colonization of former Soviet republics rich in oil and mineral resources, and to guarantee a secure pipeline for the exploitation of said resources. Instead, the altruism and democracy-spreading goodness of the American power elite are portrayed as self-evident, taking all other motives off the media table.

The necessary proof of such a conspiracy, if we choose to call it that, often turns up 25 or 50 years after the fact, when the release of classified documents churns up no public outcry or indictments. Such was the recent case with the declassified revelation that the late Connecticut senator Prescott Bush, grandfather of the current president, along with his law partner W. Averill Harriman, a former governor of New York, managed a number of concerns on behalf of Nazi industrialist Fritz Thyssen. These included the Union Banking Corporation, seized under the Trading With the Enemy Act on October 20, 1942 (Office of Alien Property Custodian, Vesting Order No. 248), Seamless Steel Equipment Corporation (Vesting Order No. 259), and the Holland-American Trading Corporation (Vesting Order No. 261).

The Knights Templar

The Union Banking Corporation financed

Hitler after his electoral losses in 1932; the other Bush-managed concerns

have been characterized as "a shipping line which imported German spies;

an energy company that supplied the Luftwaffe with high-ethyl fuel; and

a steel company that employed Jewish slave labour from the Auschwitz concentration

camp." Fuller details are documented in George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography,

by Webster G. Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin; in Kevin Phillips's American

Dynasty: Aristocracy, Fortune, and the Politics of Deceit in the House

of Bush; as well as in the colorful, conspiracist history Fleshing Out

Skull & Bones, by Anthony Sutton et al., and further confirmed by John

Loftus, a former prosecutor in the Justice Department's Nazi War Crimes

Unit. Since only the Nazi partners in the Bush-Harriman interests were

permanently deprived of their frozen stock, Prescott Bush and his father-in-law,

George Herbert Walker, waltzed off with $1.5 million when the Union Banking

Corp. was liquidated in 1951. (This was, in effect, the foundation of the

Bush family fortune: once a Snopes, always a Snopes.) Briefly picked up

by the Associated Press and buried deep in the pages of American newspapers,

this half-century-late disclosure led to no media follow-up and left no

impression on the potential electorate for the 2004 U.S. presidential contest.

Contingency theorists would declare that the activities

of one Bush 50-some years ago have nothing to do with those of subsequent

Bushes. Yet the story confirms a pattern of corrupt profiteering through

abuse of power that runs continuously through the Bush family dynasty.

They would likewise find nothing "conspiratorial" about the duck-hunting

trip Vice President Cheney took with Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia

during the week of January 4, 2004, "three weeks after the court agreed

to take up the vice president's appeal in lawsuits over his handling of

the administration's energy task force" (Los Angeles Times, January 17,

2004). "I do not think my impartiality could reasonably be questioned,"

Scalia hilariously told reporters, perhaps believing they had already forgotten

his sordid role in fixing the 2000 presidential election for George W.

Bush. Perhaps the brazen lack of ethics and truthfulness displayed by everyone

in or associated with the Bush administration shouldn't be characterized

as "conspiratorial," since this implies a secrecy that Cheney et al. believe

unnecessary, given the monumental apathy and programmed ignorance of at

least half the American public. (Cheney may not want to release transcripts

of who said what, but that isn't a secret—it's a crime in defiance of American

jurisprudence. There are no secrets, only things we know about that we

don't know all the little details of.)

Hofstadter's essay, written in the aftermath of the McCarthy witch hunts and the Kennedy assassination, with an eye on the then marginal but scary realm of right-wing plot-weavers, has been eerily assimilated by a certain idling pedantry, which rummages through the historical debris of arcane conspiracist subjects (the Knights Templar, Jesuit intrigues, Freemasonry, the Illuminati, alien abductions, the Rothschilds, the Bilderberg meetings, the Knights of Malta), often recounting the same narratives at numbing length, with little fresh insight. Only a few contemporary writers drastically depart from Hofstadter's historical itinerary, or his parochial vision of America as a "pluralist democracy" whose institutional framework is essentially benign and immutably fair, rational, and systemically mistrusted only by paranoid schizophrenics. "One need only think of the response to President Kennedy's assassination in Europe to be reminded that Americans have no monopoly on the gift for paranoid improvisation," Hofstadter declared, 15 years before the U.S. House of Representatives' Select Committee on Assassinations concluded that Kennedy's murder was indeed the result of a conspiracy.

Hofstadter's prescience is amply evidenced in Michael Barkun's A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America (2003). Barkun has ingested Hofstadter's imperious tome whole, and his book does little more than regurgitate its polemical eurekas. Barkun informs us that the "essence of conspiracy beliefs lies in attempts to delineate and explain evil." Ergo Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and most other organized religions qualify as conspiracy beliefs, though Barkun neglects to say so. Barkun identifies three principles "found in virtually every conspiracy theory," to wit: Nothing happens by accident. Nothing is as it seems. Everything is connected. Clearly Freud, Plato, Leibniz, and Einstein all suffered from at least one symptom of conspiracism; fortuitously, without mentioning any of them, someone has finally exposed these thinkers as mentally ill.

Writers like Barkun are fond of inventing buzz concepts

like "improvisational millennialism," "the cultic milieu," "agency panic,"

and "stigmatized knowledge claims." The latter, according to Barkun, are

"claims to truth that the claimants regard as verified despite the marginalization

of those claims by the institutions that conventionally distinguish between

knowledge and error—universities, communities of scientific researchers,

and the like." Few besides the amply tenured and remuneratively institutionalized

would be likely to endorse Barkun's tweedy self-flattery as descriptive

of American academia—as Jane Jacobs points out in her new book Dark Age

Ahead, our colleges and universities have largely degenerated into mere

credentialing factories—and what political scientists consider a science

tends to be more a recruitment pool for think tanks, few of which trouble

to separate knowledge from error, but simply bend data to suit the particular

tank's ideological orientation.

The same impossibly murky entities are combed over in

most books on conspiracism, though some of the literature and related nonfiction

have begun to deviate considerably from consensus historicism and the Hofstadter

school. The traditional conspiracist books look backward through the jumbled

mythologies of nebulously interwoven secret societies, usually beginning

with the Bavarian Illuminati (currently a hit topic with the rerelease

of Da Vinci Code author Dan Brown's 2000 novel Angels & Demons), though

some point back to the Knights Templar, an order of monks and knights founded

by Hugh de Payens in 1118. The Templars originally occupied the Temple

of Solomon in Jerusalem and later went in for money lending; in October

1307, on Friday the 13th (a charged date ever since), the Inquisition arrested

the leader and 123 other Knights Templar, who were promptly tortured into

confessing blasphemy, black magic, devil worship, and homosexual sodomy.

It's believed by some that rather than disbanding, the Knights reorganized

themselves sub rosa and continued to influence events and the activities

of other cults.

The Illuminati are another historically shape-shifting bunch. Historians generally date their foundation as May 1, 1776, in Ingolstadt, Bavaria, by a former Jesuit and future Freemason, Adam Weishaupt. Supposedly the Illuminati infiltrated Masonic lodges and came to dominate the movement for pro-democratic secularism. The Illuminati were shut down in 1785 by the Bavarian government, but the group allegedly reconstituted itself, like the Templars, under other names, and is still active today. It's unclear what the Illuminati are active in: satanism, control of international banking, anarchism, or Communism, depending on which conspiracist you read.

Early fears of an Illuminati conspiracy were widely disseminated via Abbé Barruél's four-volume Mémoires Pour Servir à l'Histoire du Jacobinisme of 1797, in which the author, a Jesuit expelled from France with the rest of his order, claimed the French Revolution had emanated from a conspiracy of Masons, Illuminati, and "anti-Christians." A contemporaneous screed by a Scottish scientist, John Robison, Proofs of a Conspiracy Against All the Religions and Governments of Europe, Carried on in the Secret Meetings of Free Masons, Illuminati, and Reading Societies, advanced the same idea. The book became wildly popular in America, where, it is often pointed out, several Founding Fathers belonged to the Masonic order.

Hofstadter cites Federalist fears of "a Jacob-inical plot touched off by Illuminism" in the early years of Jeffersonian democracy. An anti-Masonic movement swept the country in the late 1820s and early 1830s, slightly overlapping a wave of anti-Jesuit hysteria. "It is an ascertained fact," one Protestant minister wrote in 1836, "that Jesuits are prowling about all parts of the United States in every possible disguise, expressly to ascertain the advantageous situations and modes to disseminate Popery."

Freemasonry, whose date of origin is somewhere in the

16th or 17th century, purports to be (according to its adherents) a benign

organization, albeit with a mystical element, which served for much of

the 19th century to disseminate rationalist learning among its members

in the days before public education: geometry, architecture, astronomy,

and similar subjects. Its members aren't allowed to discuss politics or

religion within the Lodge.

As Brother Roscoe Pound, a Mason and current professor

of jurisprudence at Harvard, puts it, "Every lodge ought to

be a center of light from which men go forth filled with

new ideas of social justice, cosmopolitan justice and internationality."

All the same, Masons have been periodically accused of satanism, manipulation

of global finance, and secret influence among the world's movers and shakers.

Robert Anton Wilson, in Everything Is Under Control, reports that the P2

society in Italy, founded in the 1970s (purportedly as a subsect of the

CIA's Gladio operation), which allegedly engineered the Bologna railway

bombing in 1980 and financed itself by fraud and drug running, "recruited

exclusively among third-degree members of the Grand Orient Lodge of Egyptian

Freemasonry."

Mumia Abu-Jamal, the death row activist, reports in his column that the "CIA hid massive stockpiles of weapons and explosives throughout Italy. They amassed an army of 15,000 troops in something called Operation Gladio . . . to strike vital targets and overthrow the elected Italian government if they dared to vote against Washington's will."

Well, who knows?

original located at

http://www.villagevoice.com/issues/0421/indiana.php

Conspiracy theories emanating from both the left and the right, along with the many that issue from the Planet Debby, almost invariably rely on scapegoating as a core methodology. The interdigitating shadow organizations that fill so much of conspiracy history invariably involve the Jews or the Jesuits or both. What right-wing conspiracy theory could be complete without The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and what secularist or Protestant conspiracy theory without the Jesuits thrown in? (The extreme left has its own menu of the automatically culpable, which I won't elaborate on here.)

The Jews are routinely blamed for everything (their menacing

worldwide financial reach epitomized by the Rothschilds) and held to be

responsible for heartless capitalism and godless Communism simultaneously.

Neil Baldwin, in Henry Ford and the Jews, writing of this hero of American

business mythology, describes a 1922 article from Ford's column in the

Dearborn Independent: "Within four paragraphs, the word 'control' recurs

five times, most often in connection with the Jew's annoying propensity

for business. . . . He is the perpetual alien, 'a corporation with agents

everywhere'—

a reference that brings to mind the structure of the

Ford Motor Company itself." Let's not forget ZOG, the secret Zionist world

government, a favorite fantasy of American survivalists and neo-Nazis everywhere.

While anti-Semitism

(as distinct from anti-Zionism) is a mental illness most

virulently spread today by Semites, namely Arab Islamists, there has always

been a sinister air about the Jesuit Order. Judaism discourages proselytizing;

the Jesuits were founded on Ignatius Loyola's determination to spread Roman

Catholicism all through the world. It is doubtful, though, that Jesuits

masterminded the French Revolution, as their enemies claim.

Madame Blavatsky, founder of Theosophy, stated in a letter

to A.P. Sinnett that the "greatest statesman in Europe, the Prince Bismarck,

is the only one to know accurately all their secret plottings. . . . He

knows it has ever been the aim of the Jesuit Priestcraft to stir up disaffection

and rebellion in all countries to the advancement of its own interests."

The Sarah Bernhardt of Occultism went on to accuse British statesman W.E.

Gladstone of having been "privately received into the R.C. Church by the

Pope himself." She continued: "W.E.G. precipitates his own temporary retirement

from office, in order to get . . . an overwhelming majority from the votes

of the newly emancipated laborers at a General Election. . . . He still

thinks he can, perhaps, contrive to carry a dashing scheme for handing

Ireland over so much

further into the hands of the unscrupulous agitators,

so that the next agitation will complete the severance and dismember the

British Empire—which has long been the darling scheme of the Jesuits."

Perhaps relatedly, in Lord George Bentinck: A Political Biography (1851),

Benjamin Disraeli warned the House of Commons about secret societies in

France, Italy, and Germany.

There also exists an anti-Jesuit organization that itself qualifies as a conspiratorial cult, the Catholic lay group Opus Dei, recently flushed from its lair of secrecy by Dan Brown's bestseller, The Da Vinci Code. Founded in Franco's Spain in 1928 by Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer y Albás, Opus spread worldwide; its current membership is estimated at 80,000. It was soon recognized by the Catholic Church as its first "secular" religious institution: In the early 1980s, Opus Dei was declared by Pope John Paul II to be a "personal prelature"—that is, a church entity headed by a "prelate" under no control by local bishops and dioceses. Since its founding, Opus has had only three successive leaders: Escrivá, Alvaro del Portillo, and, currently, Bishop Xavier Echevarria, a native of Madrid. Each has promoted a cult of personality.

To the horror of many Catholics, particularly the Jesuits, Escrivá was beatified in May 1992 and canonized as a "saint" in October 2002. This follower of Franco was believed to have cured a doctor of radiodermatitis caused by prolonged exposure to X-ray machinery, a "miracle" which could very well have been the result of natural healing—Pierre Curie suffered the same sort of ailment after handling radium, and it cleared up in a few weeks.

Opus members go in for self-flagellation and other rituals

of self-inflicted pain. The organization has its own list of banned books

and a hierarchy of membership levels, and is virulently opposed to abortion

and gay rights. It endorses most of the other lunatic phobias of the ultra-right

Christian Coalition. Opus Dei would not merit all that much attention,

were it not for the fact that Robert Hanssen, the FBI agent/ Russian spy,

was revealed to be a member, and that there have been plausible allegations

that Louis Freeh, the former FBI director, along with Supreme Court justices

Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, belong to Opus Dei too.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

One could go on, into alien abductions and the legendary

UFO crash site at Area 51, or Groom Lake, 90 miles north of Las Vegas (Michael

Barkun, in A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary

America, finds it suggestive that Timothy McVeigh visited the former a

year before blowing up the Oklahoma City federal building); anticipation

of the Rapture by various religious psychotics; expectation of the Antichrist's

arrival, recently announced by Jerry Falwell on national TV (he noted that

the AC would be a Jew); belief in humanoid reptiles inhabiting vast underground

tunnels; and so forth. But the current analyses of eccentric belief systems

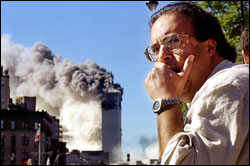

inevitably have had to take into account that the 20th century, and now

the 21st, have seen myriad authentic conspiracies unravel or partly unravel,

sometimes leaving piles of dead bodies in their wake. The Kennedy assassination,

Iran-Contra, Watergate, the CIA-sponsored overthrow and/or assassination

of Arbenz, Allende, Mussadegh, Sukarno, Lumumba, and dozens of other democratically

elected or potentially electable progressive leaders, the Enron scam, B.C.C.I.,

the sinister workings of the Carlyle Group—there is too much of the real

stuff around for a thinking person to dismiss certain apprehensions as

"paranoid." Especially since 9-11, the consensus model of thinking about

America as a Norman Rockwell painting with a few unsightly threads dangling

from the canvas has reached a nadir of popularity and credibility.

In an introductory essay, Peter Knight, editor of the 2002 collection Conspiracy Nation: The Politics of Paranoia in Postwar America, attributes modern conspiracism to "the pervading sense of uncontrollable forces taking over our lives, our minds, and even our bodies." He writes that "conspiracy thinking has become not so much the sign of a crackpot delusion as part of an everyday struggle to make sense of a rapidly changing world." In effect, individuals are losing their sense of agency in a period of political chaos and technological overload, compulsive consumerism and fear of the future, experiencing a loss of self and a sense of interchangeability with other digitized and horrifically surveilled humans, unable to get the big picture into focus and hence fixating on an idea of the world itself as a vast, impenetrable conspiracy. The worst thing about the above catalog of alienation effects is that it seems irreversible and inescapable.

Knight's book is well worth reading, as its contributors differentiate critical inquiry and skepticism from "paranoia." They problematize the friction between conspiracism and contingency theory, and the way these opposites interpenetrate; they deal with American pop culture far more knowingly than Barkun; their references encompass Lacan, Jameson, Althusser, and Zizek, among others. Especially worthwhile are Skip Willman's "Spinning Paranoia: The Ideologies of Conspiracy and Contingency in Postmodern Culture," Ingrid Walker Fields's "White Hope: Conspiracy, Nationalism, and Revolution in The Turner Diaries and Hunter," and Eithne Quinn's " 'All Eyez on Me': The Paranoid Style of Tupac Shakur." The tendency to pathologize vigorous opposition to the status quo crops up here and there more as a reflex than a position.

Similarly, Timothy Melley's 1999 Empire of Conspiracy: The Culture of Paranoia in Postwar America illustrates "agency panic" as woven into post-war American fiction and nonfiction—Joseph Heller's Catch-22, Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49 and Gravity's Rainbow, and works by Burroughs, Ishmael Reed, Don DeLillo, and many others. He acknowledges the establishment bias of traditional conspiracy critique, yet often brings to mind Mary McCarthy's remark that criticizing Burroughs's style is like criticizing the sartorial manifestations of someone banging on your door to tell you your house is on fire.

"Because the convictions I have been describing usually arise without much tangible evidence," Melley sensibly writes, "they often seem to be the product of paranoia. Yet they are difficult to dismiss as paranoid in the clinical sense. . . . As Leo Bersani points out, the self-described 'paranoids' of Thomas Pynchon's fiction are 'probably justified, and therefore —at least in the traditional sense of the word—really not paranoid at all.' " While dutifully noting the wide influence of Richard E. Hofstadter's seminal 1964 essay "The Paranoid Style in American Politics," which rather broadly identified conspiratorial thinking as a misreading of chance and contingent events, Melley is loath to automatically apply Hofstadter's axioms to the more complex realities of postmodern culture. Still, he invokes them ambiguously, enough so that Empire of Conspiracy becomes an exercise in ambivalence about consensus politics and a meandering soliloquy about what is and isn't pathological.

Mark Fenster's 1999 Conspiracy Theories: Secrecy and Power in American Culture is easily the best recent addition to the literature of what radio and TV host Long John Nebel used to call the Way Out World. (Nebel's wife, Candy Jones, revealed under hypnosis that she had been brainwashed by the CIA and operated for it as an assassin without her wet work leaving any conscious residue in her memory.) For starters, Fenster tears much of Hofstadter's Cold War assumptions about the vitality of the American mainstream to shreds, noting that Hofstadter "applied a theory of individual pathology to a social phenomenon—an interesting, perhaps productive exercise for an analogy, but problematic if . . . one is attempting to produce a concept that can be used across history to explain, for example, populist political dissent in the 1990s." In Fenster's view, conspiracism is a direct effusion of the failures of the political system, which are at least as much "conspiratorial" as "contingent" or unintended.

There is, of course, another way of considering this: Contingency and lack of intention may often constitute an unplanned, collective conspiracy dictated by historical events and their inevitable repercussions. The essential guide to this notion can be found in Eric Hobsbawm's 1994 Amnesty International lecture, "Barbarism: A User's Guide." Hobsbawm doesn't call the historical process conspiratorial, but many of the opportunities it activates certainly are.

original located at

http://www.villagevoice.com/issues/0422/indiana.php

It's important to recognize that words like conspiracy and paranoid have limited credible application in political analysis or in everyday life. Fusing them into a single concept vanquishes malign motives behind political and business decisions that affect the lives of ordinary people. In the Gilded Age, which produced a golden age of journalistic muckraking, the public knew that amoral greed resorts to subterfuge and conspiracy, as the press was not monopolized by people feeding at the same trough as the robber barons.

"Pirates are commonly supposed to have been battered and hung out of existence when the Barbary Powers and the Buccaneers of the Spanish Main had been finally dealt with," wrote Charles Francis Adams Jr. in Chapters of Erie. "Yet freebooters are not extinct; they have only transferred their operations to the land, and conducted them in more or less accordance with the forms of law; until, at last, so great a proficiency have they attained, that the commerce of the world is more equally but far more heavily taxed in their behalf, than would ever have entered into their wildest hopes while, outside the law, they simply made all comers stand and deliver."

Adams's two reports of the Erie wars of 1868, like his brother Henry's account of the New York Gold Conspiracy (inserted between them in Chapters of Erie), are so meticulously detailed as to seem irrefutable. He unravels the intricate plotting of Cornelius Vanderbilt to wrest control of the Erie Railroad and its branches from Daniel Drew, James Fisk Jr., and Jay Gould, no slouches in the conspiracy department themselves. Chapters of Erie uncovers depths of corruption and conspiracy undreamt of in America before then and unparalleled until the G.W. Bush administration. Players in the Erie drama manipulated the stock market like a rigged slot machine, liberally purchased judges and legislators, and in one spectacular instance staged a rail collision in a tunnel north of Albany.

After an injunction issued in downtown Manhattan ordering the Drew party to cease any actions in "furtherance of said conspiracy," the Drew attorneys obtained a counter-injunction from another jurisdiction and dumped 50,000 shares of Erie stock on the market, which were instantly bought up by Vanderbilt before he learned their source; to avoid arraignment on contempt of court charges, the Drew minions fled the financial district at 10 in the morning for the safety of New Jersey:

[T]he astonished police saw a throng of panic-stricken railway directors—looking more like a frightened gang of thieves, disturbed in the division of their plunder, than like the wealthy representatives of a great corporation—rush headlong . . . in the direction of the Jersey ferry. In their hands were packages and files of papers, and their pockets were crammed with assets and securities. One individual bore away with him in a hackney-coach bales containing six millions of dollars in greenbacks.

Adams's account conjures images of the so-called perp walk that some of Wall Street's most egregious recent knaves have taken for the cameras, though contemporary financial scandals have produced little authentic reform. The agencies entrusted to cleanse the system have been as tainted as their targets. The revolving door between government jobs and corporate board seats; rampant looting as corporate S.O.P.; and the Orwellian duckspeak of a conglomerated media system are symptoms of a failing democracy.

While Adams could write frankly about the true state of affairs within America's power elite ("Mr. Justice Sutherland, a magistrate of such pure character and unsullied reputation that it is inexplicable how he ever came to be elevated to the bench on which he sits . . . "), "investigative reporting" in our era has become a desk job involving a few phone calls and the endless quoting of "anonymous sources" who are, invariably, government officials rather than ordinary citizens fearing retribution from these same officials.

Since Michael Barkun's A Culture of Conspiracy typifies the "one bad apple" approach, its opening anecdote is worth recounting:

On January 20, 2002, Richard McCaslin, thirty-seven, of Carson City, Nevada, was arrested sneaking into the Bohemian Grove in Northern California. The Grove is the site of an exclusive annual men's retreat attended by powerful business and political leaders. . . . McCaslin . . . was carrying a combination shotgun-assault rifle, a .45 pistol, a crossbow, a knife, a sword, and a bomb-launching device. . . . [He] told police he had entered Bohemian Grove in order to expose the satanic human sacrifices he believed occurred there.

The interesting detail here isn't a thwarted massacre by one of those deranged loners responsible for all political assassinations but Barkun's bland characterization of Bohemian Grove: Inexplicably, he implies, the place is a magnet for conspiracists, some of whom also suggest "that the Grove's guests include nonhuman species masquerading as human beings."

In last year's Where I Was From, Joan Didion provides a more textured and provocative description of Bohemian Grove:

By 1974 . . . one in five resident members and one in three non-resident members of the Bohemian Club was listed in Standard & Poor's Register of Corporations, Executives, and Directors. . . . The summer encampment, then, had evolved into a special kind of enchanted circle, one in which these captains of American finance and industry could entertain . . . the temporary management of that political structure on which their own fortunes ultimately depended.

It's no mystery that citizens of a country methodically eliminating its social services, waging "preemptive" wars on behalf of corporate interests, defunding education, and building more prisons than hospitals view the prevailing power structure as a public menace; that many of those citizens who can't afford health care, whose jobs have been exported to countries where slave wages and child exploitation are endemic, spill over the edge, embrace bizarre cultic notions, and believe there are "aliens among us."

One smells a metaphorical truth in McCaslin's belief that "human sacrifices" occur in Bohemian Grove's exclusive covens, typically attended by Henry Kissinger, Colin Powell, James Baker III, Bush père et fils, the Bechtels, George Shultz, the heads of the World Bank and the IMF—none, as far as I know, even vaguely troubled by human sacrifices produced by the pursuit of their own enrichment.

The word conspiracy reduces logical thought to paranoia, and it's misleading in a different sense too: Little of what we ought to know about the dealings of power is especially secret anymore. Much of the public doesn't have the ability to make obvious connections between available facts. Remove education from the public agenda and you replace the capacity for analysis with an atavistic belief in horoscopes and astrology, alien abductions and Zionist imperialism.

Everyone in an authoritarian society understands what lies beyond the pale of consensual reality. Skepticism is demonized as "conspiracy theory," evidence of real conspiracies ridiculed by mainstream media. Any rejection of received ideas is misrepresented to burnish absurdist images of conspirators as Dr. Mabuse-like lunatics gathering in dark basements and Masonic lodges.

Actual conspiracies do not involve interplanetary visitors, pod people, and the other fantasies conspiracist analysts call "stigmatized knowledge." They involve money and power, and the manipulation of appearances by powerful interests. Conspiracies can evolve over time, without highly organized or explicit planning. Indeed, the "disorganized conspiracy" transpires in increments over generations, with no consistent personnel, and requires only a continuity of anti-populist, authoritarian ideology.

Ted Nace's Gangs of America: The Rise of Corporate Power and the Disabling of Democracy charts the insidious, century-long accumulation of precedents constructed around a glaring judicial error, arising from the 1886 Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad case, that has ultimately resulted in the extension of "equal protection" under the law to corporations, and the bestowal of "civil rights" and "immortal personhood" on economic entities, including the First and other Bill of Rights amendments intended to protect human individuals. This lethal absurdity has now become extraterritorial, as GATT and WTO measures enable corporations to file suit against sovereign states whose labor or environmental laws inhibit corporate profit-taking.

Nace cites the perversion of the Fourteenth Amendment, intended to guarantee due process and equal protection of the law to the slaves newly freed under the Thirteenth Amendment, into an instrument for "the empowerment of the corporation." Per Nace: Justice Hugo Black noted that in the first 50 years of the Fourteenth Amendment's existence, " 'less than one-half of 1 percent' of cases in which it was invoked had to do with protection of African Americans, whereas 50 percent involved corporations." Nace further notes that "the person who did more than anyone else to bring about this [corporate] empowerment was Supreme Court Justice Stephen J. Field . . . [whose] older brother David . . . served as counsel for the notorious railroad barons Jay Gould and Jim Fisk."

Christian Parenti's The Soft Cage follows another "disorganized conspiracy," one that begins with the written physical descriptions on passes required for plantation slaves to travel off their owners' property, and charts the gradual extension of obligatory identification documents into the lives of virtually all citizens. (An elegant exposition of the pre-photographic methods used in 18th-century Britain to identify fugitives can be found in William Godwin's spellbinding 1794 novel The Adventures of Caleb Williams. Happily for many Southern slaves, who had secretly acquired literacy and could forge these passes, the passes themselves were usually inspected by illiterate Southern whites; British fugitives had no such luck.) Parenti's book ends, or rather continues, with the gradual morphing of mandatory ID into interface media for the panoply of visual and electronic surveillance technologies now used to amass data on virtually every individual on earth. One could say, contingently, that these temporally spaced, individually smallish corrosions of individual rights and privacy "just sort of happened," though the structural contradictions between capitalism and democracy they reflect, and the manufactured belief that the two things are identical, seem hardly the products of pure chance.

Economist Loretta Napoleoni provides an exhaustively researched account of one recent conspiracy in her book Modern Jihad:

Just as Worldcom was able to use accountancy techniques to tamper with its books, bin Laden's associates succeeded in utilizing sophisticated insider trading instruments to speculate on the stock market prior to September 11. . . . [O]n 6 September . . . around 32 million British Airways shares changed hands in London, about three times the normal level. On 7 September, 2,184 put options on British Airways were traded on the LIFFE (London Futures and Options market), about five times the normal amount of daily trading. Across the Atlantic, on Monday, 10 September, the number of put options on American Airlines in the Chicago Board Options Exchange jumped 60 times the daily average. In the three days prior to the attack, the volume of put options in the U.S. surged 285 times the average trading level. . . . Ironically, in attacking one of the symbols of Western capitalism, bin Laden may have masterminded the biggest insider trading operation ever accomplished.

According to The Independent on Sunday of October 14, 2001, "To the embarrassment of investigators, it has also emerged that the firm used to buy many of the 'put' options—where a trader in effect bets on a share price fall—on United Airlines stock was headed until 1998 by 'Buzzy' Krongard, now the executive director of the CIA. . . . There is no suggestion that Mr Krongard had advance knowledge of the attacks."

This information isn't "secret," but indicates a more

coherent motive for the September 11 attacks than the

conjuration of insane Islamists who "hate our democratic

freedoms," and who can therefore serve as pretexts for a

"war on terror" that has so far done little to protect

American citizens but has grossly enriched the corporate sponsors

of the Bush administration, such as Halliburton, Bechtel,

and myriad other interests whose emissaries revel round the campfire every

summer at Bohemian Grove. And because it reveals what modern conspiracies

are really all about, you are likely to find some garbled, discrediting

version of it on page B27 of your daily newspaper rather than above the

fold on page 1.

original located at

http://www.villagevoice.com/issues/0423/indiana.php

In recognition of creativity, integrity and excellence on the Web. |

"You'll find news links on this site you didn't even know existed".. |

|

Partners |

Main Archives & Search |

News World Order |

|

|

published

by tusk36: Altoona, Pennsylvania, U.S.A

published

by tusk36: Altoona, Pennsylvania, U.S.A

email

newsworldorder@hotmail.com